Critical thinking is about using relevant, true and connected ideas to form a carefully judged analysis. It is a vital skill whether you are defusing a bomb or making any business decision, from strategy to staff recruitment. It is also an important general skill in life too…

Critical thinking requires a search for what is true, and truth is a notoriously difficult concept. A good start is to recognise that while the truth can be fluid and difficult to pin down, lies tend to be black and white and final. This realisation, however, can lead to the search for the truth becoming the search for the absence of lies, a process sometimes referred to, derogatively, as nitpicking. This technique, however, is not enough – a set of coherent and persuasive assumptions could pass the nitpicking test yet still be wrong. In addition, an over reliance on the search for inconsistencies can result in the detection of a minor and irrelevant fault – which then leads to the rejection of the larger truth.

The search for the truth is hard because the truth is ill defined and vague – it can vary both across time and between people. For example, in the 13th Century it would have been considered an evident truth that the earth was flat. As another example, two executives can be present at the same Senior Leadership Team meeting and both come away with very different ideas about what was agreed. Both might honestly believe their recollections to be self-evidently true.

The key to navigating through this minefield of truth, mistakes and lies is to have a clear idea of how you think before you start. This allows you to audit your thinking, identify any gaps – and then work on applying all types of thinking to your search for the truth. Since truth is nebulous, reasoned and analytical thinking alone may not be enough to describe it in a given situation.

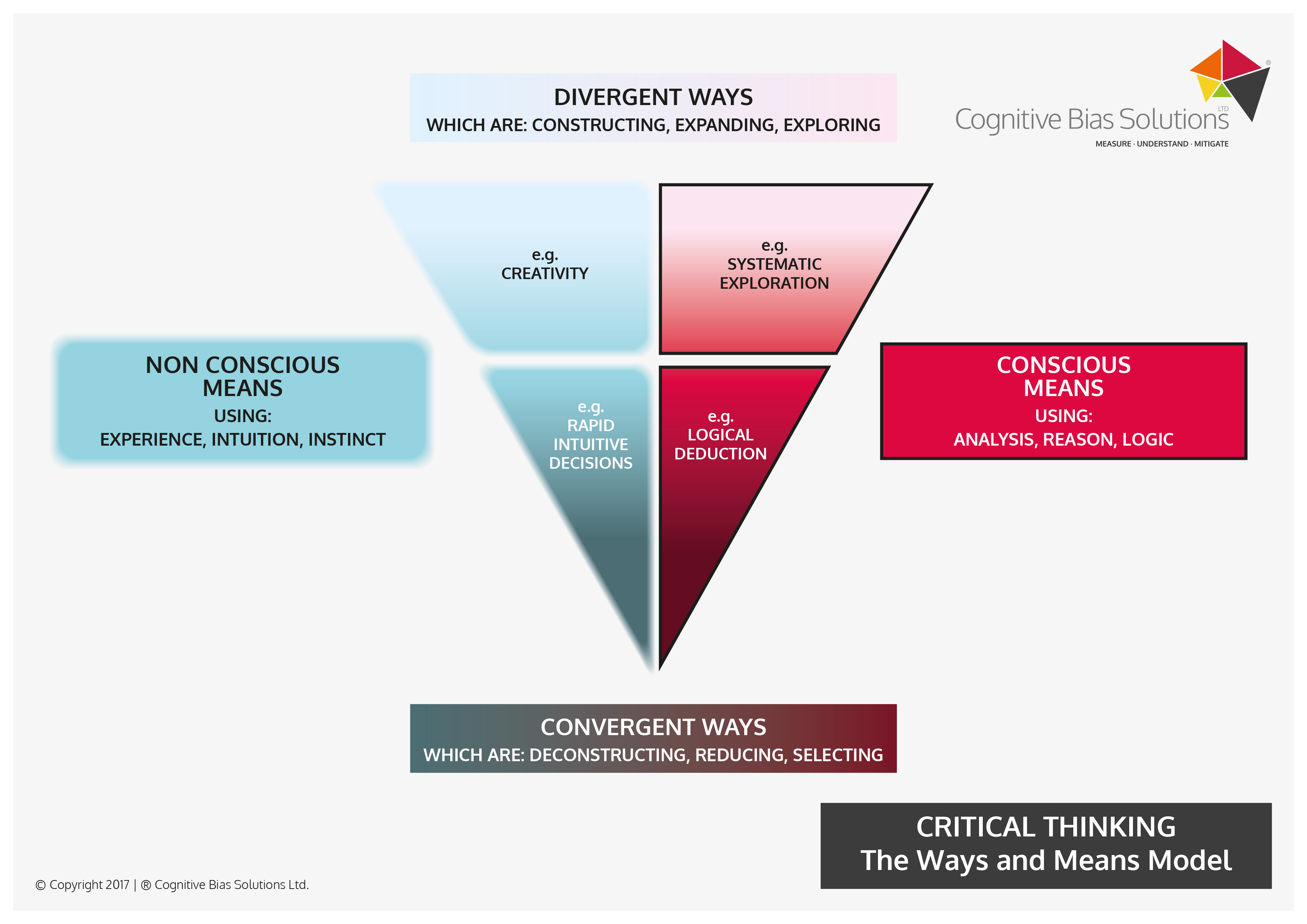

Understanding how you think is sometimes referred to as metacognition and is closely related to understanding yourself. A useful way to develop metacognition is to map your thinking against the four quadrants in the ways and means model [1].

In essence, there are two ways of thinking – convergent and divergent, and each can be approached through conscious and non-conscious means.

- Divergent ways of thinking involve exploring ideas and expanding them.

- Convergent ways involve selecting and simplifying ideas to reach a conclusion.

- Conscious means of thinking involve a deliberate and effortful use of analysis and reason.

- Non-conscious means rely on intuition, instinct and experience.

The model maps the four resulting thinking styles. Each style of thinking is equally important, and each of the four quadrants have pitfalls that you need to learn to avoid. For example, if you cannot separate fact from assumption, and cannot assemble the relevant facts that form root causes, then your conscious means/divergent ways of thinking will be flawed. Poor analytical skills will lead to your conscious means/convergent ways of thinking tending to conclusions that are wrong or don’t fully take into account potential unintended consequences.

On the other hand, both of the non-conscious means of thinking (i.e. divergently or convergently) are heavily susceptible to cognitive biases. These biases are persistent and hidden corruptions in your thinking. They can lead to false conclusions whose ‘truth’ appears completely self-evident.

Of the two non-conscious means of thinking, divergent ways/non-conscious means are extraordinarily difficult to use when you’re under pressure unless you have taken active steps to develop this quadrant beforehand. On the other hand, convergent ways/non-conscious means rely heavily on relevant, collated experience. The problem here is that convergent thinking is often used when time is short; and when you are in a hurry, all experience tends to look relevant.

It is worth remembering that this list of pitfalls in the four quadrants is not exhaustive…

All of us think differently, but it is almost certainly true that none of us think equally well in all of the quadrants of the Ways and Means Model. The secret is to understand which of the quadrants you tend to use well, then develop techniques to improve your ability in the remaining ones.

Above all, using the four quadrants to think critically as a leader is likely to make your search for the truth much more fun, effective and inspirational. The alternative is to be seen as just another single quadrant nitpicker.

[1] The model is indebted to the work of the psychologist Professor Karen Carr. See her Introduction to Thinking Skills for Leadership in Defence on the net.